Retold by Max Eilenberg

Illustrated by Niamh Sharkey

Walker Books, 2008

I like to browse the discount tables at my neighborhood bookstore. When I saw the simple illustration of Cinderella on the cover of this book, I had to take a look. As I flipped through the book I found myself enjoying the gentle illustrations of Niamh Sharkey. They're child-like (which you want in a child's book) but somehow I found them joyful and fun at the same time.

Yet however beautiful the illustrations, you have to wonder to yourself why we need yet another version of Cinderella, a classic story that has been told and re-told for hundreds of years. The answer to that is that we need this version for the adults.

This version gently fills in missing details that most children won't realize are missing. For example, if you've ever read Cinderella, have you wondered where her father went? After all, the step-mother could only be mean in the absence of the father, so what did happen to him? Another detail that most versions gloss over is the fairy godmother's rather odd request for a pumpkin. If a woman appeared out of thin air, told you that you were going to a ball, and said you should bring her a pumpkin, wouldn't that surprise you the tiniest bit? It would surprise me and in this version, In this edition, Cinderella is a bit confused by the request, too.

The little additions here are so slight and subtle that a child who knows and loves Cinderella likely will not notice the tiny differences, yet an adult will be left quietly chuckling to himself. I can't say that, as a full grown adult, I ever expected to enjoy Cinderella for its own sake but this book surprised me. It's true to the story you already know, but it's just slightly silly and that makes it even better.

Saturday, April 28, 2012

Saturday, April 21, 2012

The Hunger Games

The point of this blog is to review great books and this is not one so why am I talking about it here? Because the rest of the world thinks it is a really good read. And because this is such a wildly popular book I thought it important to share why it isn't good at all. Simply put: the writer is talented, but she does not use her talents to praiseworthy ends. So without further delay, the review.

A book about kids killing other kids that is written for the teen market? If that doesn’t grab your attention, then you must not be a parent.

The Hunger Games is the first book in a trilogy by Suzanne Collins that has, since 2008, sold more than 5 million copies. On March 23rd a movie adaptation of the first book hit theatres and made a quarter of a billion dollars in just 10 days. This is the latest big thing in teen fiction. And like Twilight before it, a pivotal element of the plot is causing concern for Christian, and even non-Christian parents: this is a story about kids killing other kids.

Deadly plot does not a bad book make

Sixteen-year-old Katniss Everdeen lives in a post-apocalyptic world where what’s left of the United States has been divided up into 12 Districts, all subservient to “the Capitol.” We learn that there was once a 13th district, but it rebelled, and in the resulting war the Capitol destroyed it. Every year since then, as show of their submission, each of the Districts has had to provide the Capitol with two Tributes, a boy and a girl, to fight to the death in a made-for-TV spectacle reminiscent of the Roman gladiatorial games. Katniss becomes the District 12 female Tribute after she volunteers to take her 12-year-old sister’s place.

Now the setting is grim, but a grim setting does not necessarily a bad book make. After all, “kids killing kids” would serve as a good summary of Lord of the Flies. In William Golding’s classic he makes use of grim plot elements to talk about Man’s depravity, and how even “innocent” children are fully capable of murder (or as the catechism puts it: “we are all conceived and born in sin”). A great writer can use a dark setting to present an important Truth.

Rooting for the anti-hero

However, Collins is no William Golding. Her premise is intriguing – the hero of our story is placed between a rock and a hard place. Since there is only one final winner in these “Hunger Games,” Katniss would seem to have a terrible decision to make: to kill or be killed?

But Katniss never makes that decision. Collins has created a moral dilemma that, on the one hand, drives the action, but on the other, is hidden far enough in the background that it never needs to be resolved. Neither Katniss nor any of the other Tributes ever consider the morality of what they are being told to do. And Collins so arranges the action that Katniss is not put in a situation where she would have to murder someone to win the game – she does kill several in self-defense, but the rest of the Tributes kill each other, and Katniss’s only immoral kill (which the author clearly doesn’t think is immoral) is a “mercy kill” near the end.

This is quite the trick, and it is the means by which Collins maintains tension throughout the book: we’re left wondering right to the end, will she or won’t she? But consider just what we’re wondering: will the “hero” of our story murder children to save her own life, or won’t she? When the plot is summarized that way, it’s readily apparent why Collins never presents the moral dilemma clearly; if it is set out in the open, it isn’t a dilemma at all. It’s wrong to murder. It’s wrong to murder even if we are ordered to. And it’s wrong to murder even to save our own lives. That’s a truth Christians know from Scripture, but one even most of the world can intuit; it is better to be murdered than to become a murderer.

Conclusion

Golding used his grim setting to teach an important Truth. Collins uses her grim setting to the opposite effect, hiding Truth, and obscuring right and wrong. She uses the mush of her relativistic worldview to hide the sinfulness of obeying obscene orders. “You have been chosen to go kill other children for the enjoyment of a viewing audience.” Confronted with such a command Collins’ unquestioning Tributes, Katniss included, bear a striking resemblance to the guards working at the German concentration camps during World War II. They, too, were just following orders.

Many people are reading The Hunger Games and that can be a reason to read a book - to be able to engage in discussions with our children or our friends about it. We can then highlight the novel's central, but obscured moral dilemma, and talk about what God would have us do. But if you are simply looking for entertainment that doesn't require much of you, this is not an edifying read.

A book about kids killing other kids that is written for the teen market? If that doesn’t grab your attention, then you must not be a parent.

The Hunger Games is the first book in a trilogy by Suzanne Collins that has, since 2008, sold more than 5 million copies. On March 23rd a movie adaptation of the first book hit theatres and made a quarter of a billion dollars in just 10 days. This is the latest big thing in teen fiction. And like Twilight before it, a pivotal element of the plot is causing concern for Christian, and even non-Christian parents: this is a story about kids killing other kids.

Deadly plot does not a bad book make

Sixteen-year-old Katniss Everdeen lives in a post-apocalyptic world where what’s left of the United States has been divided up into 12 Districts, all subservient to “the Capitol.” We learn that there was once a 13th district, but it rebelled, and in the resulting war the Capitol destroyed it. Every year since then, as show of their submission, each of the Districts has had to provide the Capitol with two Tributes, a boy and a girl, to fight to the death in a made-for-TV spectacle reminiscent of the Roman gladiatorial games. Katniss becomes the District 12 female Tribute after she volunteers to take her 12-year-old sister’s place.

Now the setting is grim, but a grim setting does not necessarily a bad book make. After all, “kids killing kids” would serve as a good summary of Lord of the Flies. In William Golding’s classic he makes use of grim plot elements to talk about Man’s depravity, and how even “innocent” children are fully capable of murder (or as the catechism puts it: “we are all conceived and born in sin”). A great writer can use a dark setting to present an important Truth.

Rooting for the anti-hero

However, Collins is no William Golding. Her premise is intriguing – the hero of our story is placed between a rock and a hard place. Since there is only one final winner in these “Hunger Games,” Katniss would seem to have a terrible decision to make: to kill or be killed?

But Katniss never makes that decision. Collins has created a moral dilemma that, on the one hand, drives the action, but on the other, is hidden far enough in the background that it never needs to be resolved. Neither Katniss nor any of the other Tributes ever consider the morality of what they are being told to do. And Collins so arranges the action that Katniss is not put in a situation where she would have to murder someone to win the game – she does kill several in self-defense, but the rest of the Tributes kill each other, and Katniss’s only immoral kill (which the author clearly doesn’t think is immoral) is a “mercy kill” near the end.

This is quite the trick, and it is the means by which Collins maintains tension throughout the book: we’re left wondering right to the end, will she or won’t she? But consider just what we’re wondering: will the “hero” of our story murder children to save her own life, or won’t she? When the plot is summarized that way, it’s readily apparent why Collins never presents the moral dilemma clearly; if it is set out in the open, it isn’t a dilemma at all. It’s wrong to murder. It’s wrong to murder even if we are ordered to. And it’s wrong to murder even to save our own lives. That’s a truth Christians know from Scripture, but one even most of the world can intuit; it is better to be murdered than to become a murderer.

Conclusion

Golding used his grim setting to teach an important Truth. Collins uses her grim setting to the opposite effect, hiding Truth, and obscuring right and wrong. She uses the mush of her relativistic worldview to hide the sinfulness of obeying obscene orders. “You have been chosen to go kill other children for the enjoyment of a viewing audience.” Confronted with such a command Collins’ unquestioning Tributes, Katniss included, bear a striking resemblance to the guards working at the German concentration camps during World War II. They, too, were just following orders.

Many people are reading The Hunger Games and that can be a reason to read a book - to be able to engage in discussions with our children or our friends about it. We can then highlight the novel's central, but obscured moral dilemma, and talk about what God would have us do. But if you are simply looking for entertainment that doesn't require much of you, this is not an edifying read.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

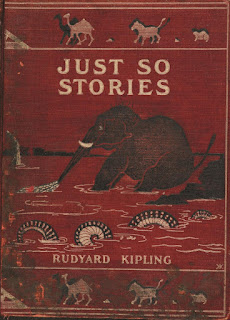

Just So Stories

by Rudyard Kipling

illustrated by the author1902 / 128 pages

A great book for fathers to read to their daughters is Just So Stories, because Rudyard Kipling actually wrote it in memory of his oldest daughter, who died of illness. In the book, he calls her his "Best Beloved," which is a good thing for fathers to call their favorite daughters (all of them, of course) as they read, for instance, how a father and his daughter invented the alphabet.

There are some details that merit caution. Some stories need pre-reading – since they feature “gods” and djinns and a magic-wielding King Solomon, or a somewhat stereotyped Ethiopian character – to see if parents want to read them to their daughters (or sons).

However, the moral lessons taught are always sound. For instance, when there are people in the stories, the tales assume that man is meant to "have dominion" over creation, as God commands in the creation mandate of Genesis 1, and as David wonders at in Psalm 8. (SPOILER ALERT!) As an example, the Camel's refusal to work for the man is what eventually gets him his "humph." The Whale's tiny throat results from his swallowing a mariner with "infinite-resource-and-sagacity and the raft and the jack-knife and his suspenders, which you must not forget."

That last phrase – "infinite-resource-and-sagacity" – is the sort of vocabulary that Kipling loves to use in the Just So Stories. Kipling's word choice may challenge both parent and child as you read it aloud (look it up if you need to!), but it the quotation above is also a catchy refrain. Kipling's catchy catchphrases will stay in your mutual vocabulary as the best kind of private joke that readers of a classic tale can share.

The version shown here also has Kipling's original illustrations, which have the charm of showing how a father with an endlessly inventive mind, and drawing skills that almost (but not quite!) match his imagination, explains the 'good part' of the story to his young daughter, including the invention of the letters of the alphabet, as seen through her child's view of the world.

In conclusion, this is a book I have read aloud to children in my family, both at six years old and at eight - but like any intelligent children's classic, you could also read it to much older children who will appreciate its charm and humor. Highly recommended.

illustrated by the author1902 / 128 pages

A great book for fathers to read to their daughters is Just So Stories, because Rudyard Kipling actually wrote it in memory of his oldest daughter, who died of illness. In the book, he calls her his "Best Beloved," which is a good thing for fathers to call their favorite daughters (all of them, of course) as they read, for instance, how a father and his daughter invented the alphabet.

There are some details that merit caution. Some stories need pre-reading – since they feature “gods” and djinns and a magic-wielding King Solomon, or a somewhat stereotyped Ethiopian character – to see if parents want to read them to their daughters (or sons).

However, the moral lessons taught are always sound. For instance, when there are people in the stories, the tales assume that man is meant to "have dominion" over creation, as God commands in the creation mandate of Genesis 1, and as David wonders at in Psalm 8. (SPOILER ALERT!) As an example, the Camel's refusal to work for the man is what eventually gets him his "humph." The Whale's tiny throat results from his swallowing a mariner with "infinite-resource-and-sagacity and the raft and the jack-knife and his suspenders, which you must not forget."

That last phrase – "infinite-resource-and-sagacity" – is the sort of vocabulary that Kipling loves to use in the Just So Stories. Kipling's word choice may challenge both parent and child as you read it aloud (look it up if you need to!), but it the quotation above is also a catchy refrain. Kipling's catchy catchphrases will stay in your mutual vocabulary as the best kind of private joke that readers of a classic tale can share.

The version shown here also has Kipling's original illustrations, which have the charm of showing how a father with an endlessly inventive mind, and drawing skills that almost (but not quite!) match his imagination, explains the 'good part' of the story to his young daughter, including the invention of the letters of the alphabet, as seen through her child's view of the world.

In conclusion, this is a book I have read aloud to children in my family, both at six years old and at eight - but like any intelligent children's classic, you could also read it to much older children who will appreciate its charm and humor. Highly recommended.

Many version can be had, including this one from Amazon.com, and this from Amazon.ca.

Saturday, April 7, 2012

The Journey

A Spiritual Roadmap for Modern Pilgrims

by Peter Kreeft

InterVarsity Press, 1996, 128 pages

This is an allegorical journey, reminiscent of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. But in this case, the pilgrim - the author Peter Kreeft - has Socrates as his guide. And instead of facing trials and temptations on the road, he runs into one Greek philosopher after another, every time there is a fork in the road. Each one of them offers up their own particular worldview for consideration and Kreeft then has the choice of either staying with them, and subscribing to their philosophy, or rejecting it, and continuing on his journey in search of Truth.

Though these philosophies are ancient, they are also current. Take as example the first philosopher Kreeft and Socrates meet: Epicurus presents the "Eat, drink and be merry." He tells Kreeft that the Truth isn't even worth seeking after - not when there is so much partying to do! Today we might call this the Hugh Hefner philosophy - why think about things such as Truth and the purpose of life, when there is yet another woman to bed, more money to be made and spent, and more parties to attend. And indeed, when the pilgrim rejects this worldview, he notices that Epicurus bears a strong resemblance to Hefner.

As he continues he meets more ancient Greeks, each with their own challenge to present, and each with their own modern day counterpart. This is what makes the book a valuable tool. Just as Socrates is a guide to the pilgrim Kreeft as he is confronted with ten different errant worldviews, so too this book can serve as a guide to anyone bumping up against these worldviews today. Some of the philosophers he meets include:

One note of caution: the author is Catholic, and in this book that comes out in an Armininan flavoring to some passages. But Kreeft is also a great thinker, and when he targets secular errors, as he does in this book, there are few writers his equal. He has a whole series of books that feature Socrates and his questioning method, including The Unaborted Socrates: A Dramatic Debate on the Issues Surrounding Abortion and the Best Things in Life

and the Best Things in Life , both of which I would also recommend. But Kreeft is also a dedicated apologist for the Roman Catholic church and has written innumerable books on that subject too, so I would not recommend all his books with equal enthusiasm and would warn off an undiscerning reader from most of them, these three excepted.

, both of which I would also recommend. But Kreeft is also a dedicated apologist for the Roman Catholic church and has written innumerable books on that subject too, so I would not recommend all his books with equal enthusiasm and would warn off an undiscerning reader from most of them, these three excepted.

That said, this particular title would be perfect for anyone in university, or heading there, as a great tool to help them see through and answer the secular worldviews they'll run into on campus.

InterVarsity Press, 1996, 128 pages

This is an allegorical journey, reminiscent of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. But in this case, the pilgrim - the author Peter Kreeft - has Socrates as his guide. And instead of facing trials and temptations on the road, he runs into one Greek philosopher after another, every time there is a fork in the road. Each one of them offers up their own particular worldview for consideration and Kreeft then has the choice of either staying with them, and subscribing to their philosophy, or rejecting it, and continuing on his journey in search of Truth.

Though these philosophies are ancient, they are also current. Take as example the first philosopher Kreeft and Socrates meet: Epicurus presents the "Eat, drink and be merry." He tells Kreeft that the Truth isn't even worth seeking after - not when there is so much partying to do! Today we might call this the Hugh Hefner philosophy - why think about things such as Truth and the purpose of life, when there is yet another woman to bed, more money to be made and spent, and more parties to attend. And indeed, when the pilgrim rejects this worldview, he notices that Epicurus bears a strong resemblance to Hefner.

As he continues he meets more ancient Greeks, each with their own challenge to present, and each with their own modern day counterpart. This is what makes the book a valuable tool. Just as Socrates is a guide to the pilgrim Kreeft as he is confronted with ten different errant worldviews, so too this book can serve as a guide to anyone bumping up against these worldviews today. Some of the philosophers he meets include:

- The Skeptic

- The Cynic

- The Nihilist

- The Materialist

- The Relativist

- The Atheist

- The Pantheist and Deist

One note of caution: the author is Catholic, and in this book that comes out in an Armininan flavoring to some passages. But Kreeft is also a great thinker, and when he targets secular errors, as he does in this book, there are few writers his equal. He has a whole series of books that feature Socrates and his questioning method, including The Unaborted Socrates: A Dramatic Debate on the Issues Surrounding Abortion

That said, this particular title would be perfect for anyone in university, or heading there, as a great tool to help them see through and answer the secular worldviews they'll run into on campus.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)